Healthy vs. Harmful: Which Physical Activities Truly Benefit Your Health (And Which Don't)

Goal: Identify which activities benefit health-and which do not

Many people ask a version of the same question: physical activities that are beneficial to health include all but which of the following? The core idea is to separate evidence-based, health-promoting movement from activities that offer little benefit-or may be harmful without safeguards. Below you’ll find a practical, research-backed guide to what counts as beneficial, what doesn’t, how much you need, and how to start safely.

What counts as health-beneficial physical activity

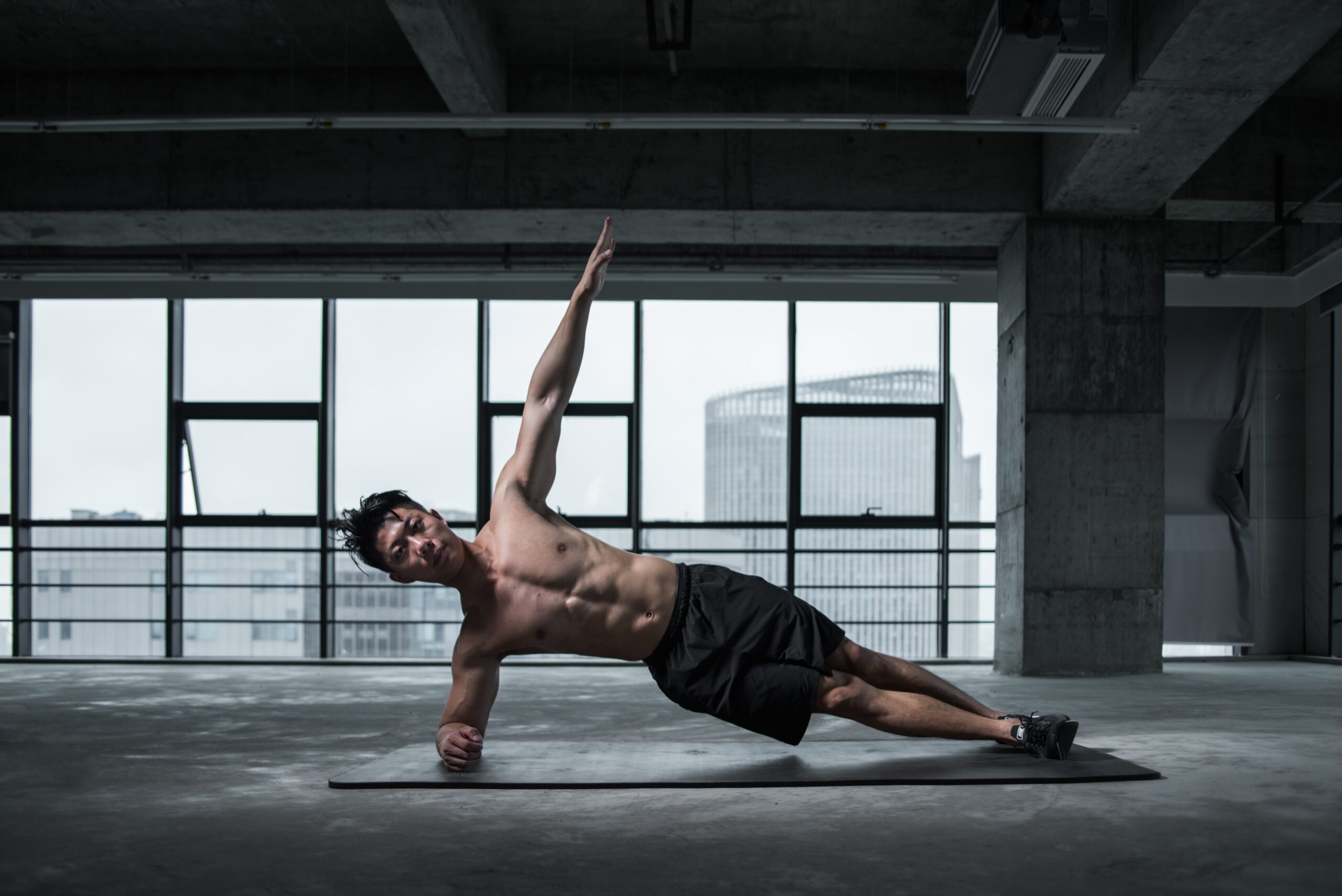

According to leading public health and clinical sources, a wide range of activities improve health when done regularly and safely. These include moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity (such as brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or jogging), muscle-strengthening (such as resistance training or bodyweight exercises), balance work, and flexibility training. Benefits span weight control, lower cardiometabolic risk, improved mood, better sleep, and reduced mortality risk [1] [2] [3] .

Key takeaways supported by current guidance: adults gain measurable protection from heart disease and stroke with at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, with additional benefits at higher volumes; resistance training further reduces risk and improves function; even smaller amounts than 150 minutes can still confer benefit when done consistently [1] .

Activities that are

not

beneficial (or may be harmful) without safeguards

While most movement is positive, certain patterns may offer little health benefit or carry avoidable risk:

1) Inactivity and prolonged sedentary time. Being largely inactive is associated with higher risks of chronic disease and worse outcomes; even light-to-moderate movement improves markers of health compared to doing little or nothing [1] [2] .

2) Excessive, exhaustive training without progression or recovery. Very intense, exhaustive activity can increase oxidative stress and may contribute to overuse injuries if not balanced with recovery and proper programming; moderate, regular training is associated with better net health outcomes [4] .

3) High-risk techniques performed with poor form. For example, heavy resistance moves or plyometrics done without instruction can lead to injury, offsetting potential benefits. Evidence supports strength training as beneficial when performed with appropriate load, technique, and progression [3] [2] .

4) Activities paired with unhealthy behaviors. Exercise does not negate harms from smoking, sleep deprivation, or unsafe practices. Conversely, being active can assist smoking cessation by reducing cravings and withdrawal symptoms, magnifying overall benefit when paired with quitting efforts [3] .

In short, the best answer to “beneficial include all but which?” is that inactivity and unsafe, excessive, or improperly executed activity are not health-beneficial, while appropriately dosed aerobic, strength, balance, and flexibility work are beneficial across populations [1] [2] [3] [4] .

Source: prohealthuc.com

Evidence-backed benefits you can expect

Cardiovascular and metabolic health: Regular activity helps lower blood pressure, improve HDL cholesterol, and reduce risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Improvements begin even below 150 minutes per week and grow with additional activity [1] [2] .

Cancer risk and survivorship: Physical activity lowers risk for several common cancers and improves quality of life for survivors, with supportive mechanistic explanations such as improved body composition and lipid profiles [1] [5] .

Mental health, cognition, and sleep: Exercise supports mood, reduces anxiety, helps manage depression risk, enhances cognitive function with aging, and improves sleep onset and duration [3] [2] .

Functional strength, bones, balance: Resistance training strengthens muscles, while weight-bearing and balance work support bone density and reduce falls in older adults [3] [1] .

Infectious disease outcomes: Physical activity is associated with better outcomes in illnesses such as COVID-19, flu, and pneumonia, with active individuals having lower risk of severe events in reviewed studies [1] .

How much and what type: a practical weekly blueprint

Use this simple, flexible plan that aligns with public health guidance:

Aerobic target: Aim for 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity (e.g., 30 minutes, 5 days/week), or 75 minutes of vigorous activity. If you’re currently inactive, start with 10-15 minutes and build up; benefits accrue even below 150 minutes when you are consistent [1] .

Strength training: Two nonconsecutive days per week covering major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, chest, core, shoulders, arms). Start with 1-2 sets of 8-12 repetitions focusing on technique and slow progression [3] [2] .

Balance and mobility: Include 10-15 minutes, 2-3 times per week, of balance drills (e.g., single-leg stands, heel-to-toe walks) and gentle range-of-motion work. This is especially valuable for older adults to reduce fall risk [3] .

Recovery: Schedule at least 1-2 lighter days weekly. Watch for signs of overreaching (persistent fatigue, sleep disruption); adjust volume and intensity accordingly [4] .

Step-by-step: build your plan safely

Step 1 – Baseline check: If you have chronic conditions, recent surgeries, or concerning symptoms (e.g., chest pain, dizziness), consult a licensed clinician before starting or progressing activity. You can find clinicians through your health plan’s provider directory or by contacting your primary care clinic.

Step 2 – Set SMART goals: For example, “Walk 20 minutes at a moderate pace, 4 days this week.” Track with a simple log to build momentum.

Step 3 – Choose low-friction options: Brisk walking, stationary cycling, or swimming are joint-friendly and scalable. Add short bouts across the day if scheduling is tight; all movement counts toward your total [2] .

Step 4 – Progress gradually: Increase time by about 5-10 minutes per week, or intensity by one small step (e.g., from easy to moderate). For strength, add small increments in load only after you can complete all reps with stable form.

Step 5 – Balance your week: Combine 3-5 aerobic sessions, 2 strength sessions, and brief mobility/balance segments. Keep at least 48 hours between heavy strength sessions for the same muscle group.

Step 6 – Mind recovery and sleep: Quality sleep and rest days improve adaptation and reduce injury risk; activity also supports better sleep continuity [3] .

Step 7 – Troubleshoot setbacks: If pain arises, scale volume or choose low-impact alternatives (e.g., pool workouts). If motivation dips, set smaller goals or add social accountability (walking partner, group class).

Examples and safe alternatives

If running causes joint pain: Swap in cycling, elliptical, or deep-water running. Maintain intensity with intervals (e.g., 1 minute brisk, 2 minutes easy) while protecting joints.

If you’re new to strength training: Begin with bodyweight squats to a chair, wall push-ups, hip hinges with a dowel, and supported rows. Focus on control, full range, and breathing. Progress by increasing repetitions, then external load.

If balance is a concern: Practice near a stable surface, start with two-hand support, and reduce support gradually. Integrate heel-to-toe walking and single-leg stance for 10-30 seconds, building over time [3] .

If time is limited: Use micro-bouts-three 10-minute brisk walks or two 15-minute cycling sessions. Evidence indicates accumulating activity across the day still supports health benefits [1] [2] .

Common pitfalls that reduce benefits

All-or-nothing thinking: Skipping movement because you can’t do a full workout reduces total benefit. Even short sessions matter and add up over time [2] .

Ignoring strength and balance: Relying only on cardio leaves functional gaps. Add two brief strength sessions and simple balance drills to round out your plan [3] .

Pushing intensity too fast: Rapid jumps in volume or load raise injury risk and can provoke excessive fatigue. Follow gradual progression and prioritize form [4] .

Answering the original question clearly

Beneficial physical activities include moderate-to-vigorous aerobic exercise, strength training, balance work, and flexibility exercises done regularly and safely. They do

not

include inactivity, and they do

not

include unsafe, exhaustive, or poorly executed movements that elevate risk without added health benefit. In practical terms, choose sustainable, progressively dosed activity across the week and avoid extremes or improper technique

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

.

Source: thegypsynurse.com

How to get support without risking bad information

If you’re unsure about local programs or classes, consider these steps rather than relying on unverified links:

1) Contact your primary care provider’s office and ask for referrals to community fitness programs or physical therapy if you need supervised exercise. 2) Check your health insurer’s member portal for wellness benefits-many plans include access to gym networks or virtual fitness at reduced cost. 3) Search for “community center fitness classes” or “senior balance classes” in your city’s official parks and recreation department website. Use the city’s official site to avoid third-party sign-up fees. 4) If you have a condition (e.g., diabetes, arthritis), ask your clinician about disease-specific exercise programs offered by hospitals or certified community providers.

References

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024). Benefits of Physical Activity.

[2] Mayo Clinic (2023). Exercise: 7 benefits of regular physical activity.

[3] MedlinePlus (2024). Benefits of Exercise.

[4] Healthline (2017, regularly updated). Exercise: The Top 10 Benefits of Regular Physical Activity.